Welcome back for another Cup of Tea With Ethel Turner, which once again, isn’t anything to do with Ethel Turner. I just wanted to share another one of Madeleine Board’s short stories. Two Birds With One Stone was published in 1924, the year she got married (which is perhaps rather fitting).

For those of you who have never stepped foot in Australia, this story is set in Western New South Wales. Settlers lived on smaller blocks of land they called selections. I’m not sure whether I’d go so far as to say they were “farms”. It seems many of them were more of a wish and a prayer, especially during times of drought. They were often very isolated, and struggled for the basics. There was also conflict with the indigenous Australians, which doesn’t always rate a mention. This is grinding hardship without a lot of hope. They’re waiting for the rain. Although it doesn’t actually state where it is set, the uncle’s gone droving cattle to Gilgi, which is near Coonamble in the State’s far North-West and Goorong is near Wellington. To me, the story reminds me very much of Henry Lawson’s stories of families struggling on their selections: “The Drover’s Wife”, “Water Them Geraniums” and a poem: “Past Carin'”

So, without further ado, here’s:

Two Birds With One Stone

“What’s to stop you coming away with me to-night, Annie?” Bill Preston asked, persuasively. “Your uncle’s gone with the cattle to Gilgi, and won’t be back for a week. Now’s your chance. She couldn’t stop you.”

“I’m not afraid of her,” Annie answered with scorn. She clenched her fists involuntarily, and Bill was quick to catch the inference.

“You’d flatten her if she tried!” He exclaimed admiringly.

His eyes wandered over the girl’s tall figure appraisingly. The badly cut dress of coarse material could not hide its perfection, though the beautifully formed arms were burnt and freckled, due to the rough outdoor life Annie led on her uncle’s selection.

‘You don’t love me,” he said, watching her face.

The girl made a nervous gesture with her strong hands.

“It’s not that,” she said miserably, with a sharp intake of breath.

“What is it, then?”

Annie’s eyes wandered over the burnt-up paddock to the weatherboard homestead in the distance, built on a gentle rise. It had the same parched look as everything around.

“I hate that place,” she said passionately. “Its burning tin roof, its creaking timbers. The miserable rooms stifle me! I hate the flies, and mosquitoes. I hate Aunt Hannah and her crowd of wretched kids! What’s she ever done to make me like her? She’s told me pretty well every day since I’ve been old enough to understand, what my mother done, and what I am because of her.”

She turned to Bill, eyes burning.”You know, as well as everyone else in the district! Uncle’s knocked her down more than once for saying it in front him. I’ve slaved, for them ever since I was a little thing, and the last few years I’ve saved uncle a man’s wages.”

Her passion stirred Bill to fever heat.

“That’s just it. Why continue to be a slave when there’s a chance of something better offering with me?” he demanded.

Annie Marden’s troubled gaze rested on his face, but she disregarded the question.

“They wouldn’t have given me any schooling, only I made them. When I was 10 I walked 20 miles one day to put the teacher at Goorong wise about me not learning, and then aunt and uncle had to let me be taught.”

She paused. Bill’s gaze was upon her lips anxiously.

“All the same, I can’t go with you—yet,” she said. “They’d be ruined sure then. Wait until the rain comes, and uncle can afford to pay for help. He could never do all the work of this place himself. The boys are no use: they’re not old enough, and they’re as lazy as pigs,”

“Let your aunt work like they’ve made you—her and her six ugly sons.”

“Bill,” Annie pleaded, putting her hand gently across the bitter mouth. “She can’t. All the strength and energy’s gone out of her. The bush is cruel most always, it seems to me, but when there’s a drought, to those who never had much, it’s just hell, the struggle to go on living.”

Her big eyes were sombre, and her bosom rose and fell quickly with tremulous breathing.

“You don’t want me,” cried Bill. “That’s what it is!”

Annie caught his hand fiercely, crushing it against her heaving breast.

“Bill, don’t say that! You’re the only one I have ever cared for, that has ever bothered about me. Be patient, dear, for a little while. When the rain comes I’ll go with you, and we’ll be married. Can’t you wait?”

‘”No,” he said roughly, pushing her aside.

“It’s now or never.”

He shaded his face with his hand in an attitude expressing the deepest dejection, and when he spoke his voice trembled.

‘When I went to the war you were a long-legged, wild girl, with plaits of wonderful hair. You didn’t seem to mind when I said good-bye, but I remembered you all the five years I was away. I swear you weren’t ever out of my thoughts,” he lied convincingly. “When I came back, it was only to you. But evidently you wouldn’t have cared if I’d been killed.”

“Bill!” she protested, in piteous accents.

With a quick movement he put his arms round her, holding her closely, His black eyes gleamed feverishly.

“Come with me, Annie, to Sydney, where we’ll be married. I swear it. We’ll take a flat near the sea—you’ve never seen it. I’ll buy you pretty dresses and hats, and you’ll look lovely. Life there’ll be wonderful after the heat and drought of this, cursed place.”

The sullen mouth trembled into a wondering smile, a pink flush stained the freckled cheeks. Her heart hungered for love, for kindness, which she had never known. She pressed her face against his: “I’ll go with you tonight,” she whispered.

“At 8 o’clock I’ll wait for you with a couple of riding horses on the track by the old sliprails,” he told her exultantly.”Don’t bother to bring anything, except what you’ve got on now. I can buy whatever you want.”

She caught him by the shoulders, the light in her eyes giving place to a searching, anxious expression.

“Where’ll you get the money from? You’re not thinkin’ of your father’s plant you told me of? You’d never stoop to steal, Bill?”‘she questioned.

He forced a laugh that rang out among the trees.

“What a silly girl you are! Why I got my war bond cashed.”

His glance flitted furtively from post to post of the fence. What awkward questions she put.’ She would soon be cured of that, however, when she was his.

At 10 minutes to 8 o’clock that night, in the small, stifling living-room of Marden’s homestead. Annie faced her aunt. Her dress was the coarse galatea of the afternoon, with a black, straight-brimmed hat above her reddish hair. The small parcel in her hands contained a change of under clothing and a nightgown. Unbeautiful garments they were, of calico, washed the previous week in stagnant, muddy water (but how precious!) from the almost empty well.

“I’m going with Bill Preston to-night to Sydney to be married,” she said jerkily.

Her aunt was seated at a rickety table, adding another patch to an already heavily burdened pair of knickers belonging to one of her boys. The one meagre window was wide open, but the air that came in from outside only added to the heat of the room.

“You are, are yer?” returned Aunt Hannah, her voice full of acidity, as she took another stitch.

The little Mardens, playing a noisy game of “jacks” on the floor, left off for a few seconds to listen.

“Yes, I don’t owe you anything. I’ve paid for the food I’ve had over and over again with these hands, and the bedding, an’ clothing, such as it’s been.”

The girl spoke coolly, but her legs were trembling.

“Tommy, shut up yer noise, or I’ll knock yer ‘ed off!”

The little woman, so thin that there seemed no flesh on her limbs, only skin drawn over the bones, put her work on the table, raising her lifeless eyes to her niece’s flushed face.

“So yer goin’ to marry that waster, Bill Preston,” she remarked.

Her niece gave a curt nod, and she drew her bloodless lips into a tight line.

“Don’t gull yerself that he’ll marry you! He’s only runnin’ yer, to get yer like yer mother was got.”

“Were’s she goin’ to, mum?” the eldest little Marden cut in, bobbing his wizened face up at his mother’s side.

He subsided instantly with a red mark on his forehead, evidence of the impress of his mother’s knuckles.

“Bill Preston is going to marry me, and, what’s more, buy me pretty things to wear, and I’m going this instant to meet him. He’s waiting with the horses,” Annie cried resentfully, all nervousness disappearing under the sting of her aunt’s words.

“You are, are yer?”

“If you don’t leave off pinchin’ Jackie I’ll break every bone in yer body,” she threatened her second son in exactly the same tone of voice.

Then she jerked herself up from the hard wooden chair, and, arms akimbo, faced her niece. Her prematurely grey head wagged from side to 6ide as she craned her neck upward, talking fast and violently.

“You don’t go out of this ‘ome till yer married proper—if any man is ever mad enough to want yer for ‘is wife. Yer mother mussed ‘erself up. an’ you ain’t goin’ to do the same, if I have a say, an’ don’t for one moment imagine that you ire! If yer uncle was ‘ere you’d be crawlin’ round doin’ as you was told. You think because I’m small that I ain’t no match for yer, and yer can cut off, but you won’t, Annie Marden!” _

As the shrill voice ceased, silence descended upon the miserable room. Such excitement was unknown in the lives of the six little Mardens. Even the youngest, aged two and eight months, sat perfectly still and mute on the floor, his pale blue eyes open their widest.

Annie took a couple of quick steps— threatening steps—in the direction of her aunt.

“Good-bye. P’rhaps you’d like to give me a kiss, as it’s the last time you’ll ever have the pleasure of seeing me! No! I didn’t think so! I won’t try the kids. They’re too dirty to go within yards of.”

She made for the door, but her aunt was there first. Banging it to, so that the timber of the whole place shook, she stood with her back pressed against the boards. Annie, tall and fine, stooped over her, scorn in her face.

“I could bundle you out of that with one little twist of my wrist,” she said. “You know that, but I won’t; I might hurt you in my present mood. The window’ll do me.’!

“On to ‘er! ‘Old ‘er! Don’t let ‘er go or “I’ll murder yer!” the mother shrieked across the room to her brood.

Before the girl had a chance to make her exit through the window the six had fastened to her, the older boys with the grip and tenacity of bull pups.

“I’ll do for the lot of you if you don’t leave go,” she cried violently, and commenced to use her fists.

But the youngsters were used to blows. It was not because of their mother’s shrill command, or because they bore their tall cousin any grudge, that they held on. It was just for the excitement of the thing— to break the deadly sameness of their existence.

Without a murmur they took the unmerciful cracks and blows delivered in the wild tumble round the tiny room. The table was upset, and the dilapidated chairs sent sprawling.

“Let ‘er go! Come ‘ere behind me! Quick!” their mother’s voice rose shrilly from the doorway. ….

Panting and bleeding they obeyed the order.

Annie Harden leaned against the wooden wall, struggling for breath. Her dress was torn in many places, and her arms were scratched and bruised. She bled profusely from a wound on the neck, where one of her young cousins had fastened his sharp teeth. Her hat was a mangled thing on the floor, and her bright hair hung in a dishevelled mass about her shoulders and down her back. In the smoky light of the kerosene lamp, suspended above the fire-‘ place by the aid of a nail, her eyes glared across the room to where the frail figure of her aunt was barely discernible in the darkness of the doorway.

“You’ll pay for this one day, you and those brats. of yours!” she cried. The passionate. voice could have been heard outside yards distant.

“I’ve said it before, an’ I’ll say it again. You don’t go, Annie. You don’t leave yer ‘ome!”

There was a loud report, and the girl crumbled into a heap on the floor.

Aunt Hannah ran forward, a smoking gun in her hands.

Twelve little Marden eyes bulged, as six small bodies followed in a bunch.

Their mother stood the old gun in a corner, and hurried across to the limp form of her niece.

“Tommy, a drop or two of water, quick! Use the pannikin, an’ be sure not to spilt any or I’ll knock yer ‘ed off. She’s only fainted.”

After a minute or so the girl’s eyes opened. She gazed wildly into the face above. The sullen mouth quivered, and Annie burst into a passion of weeping, hiding her face in her bruised hands.

Aunt Hannah touched the bowed head awkwardly, as it she had long forgotten how to caress.

“There, there, you’ll be all right, Annie girl. It’s only yer leg that’s ‘urt.”

Afterwards, as she returned the gun to its place in an outhouse, her dirty sons leaping and screaming, unheeded about her, she mumbled to herself: “I ‘ad to do it. Who’d ‘aye done the ploughin’ and sowin’ and reapin’ when the rain comes, an’ lookin’ after the sheep, now? Better to ‘ave her useless for a week or two. And, any ow, Annie Marden, yer Bill Preston’s own sister!” 1.

…..

So, what did you think of Two Birds With One Stone? I’ll leave you all to formulate your own thoughts, and I’ll join you in the comments. Meanwhile, I’d like to encourage you to check out some of Henry Lawson’s works which could well be an influence behind this story. I’ve listed a few below, and if you struggle with any the cultural references, I’m only too happy to help.

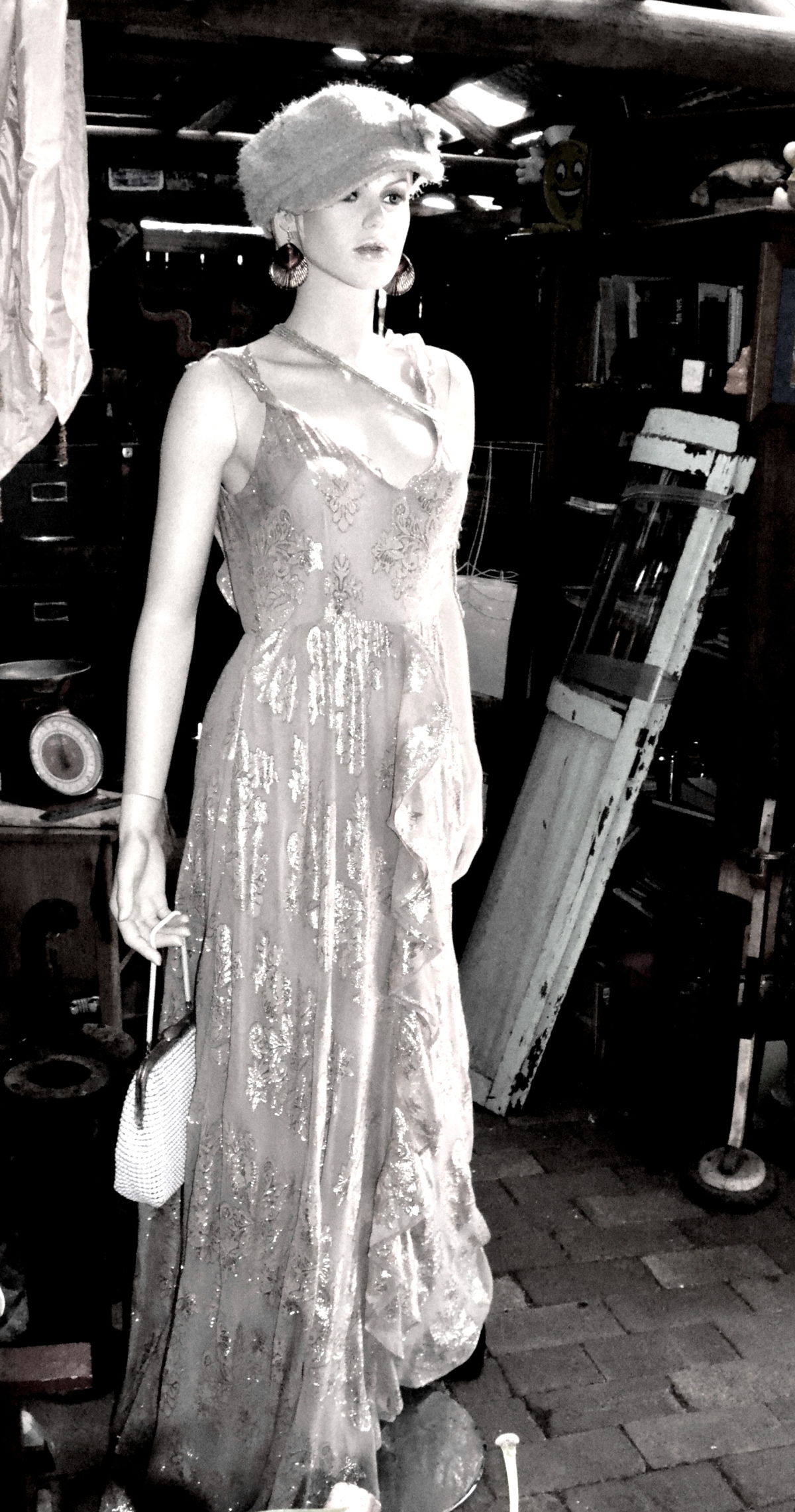

I hope you feel the photograph somewhat suits the story. I spent hours tonight scouring old Australian paintings trying to find something suitable, and there was nothing. The photo was taken at a vintage shop at Wollombi about an hour’s drive North of here. At least she looked like she was going somewhere.

Considering this story is set out in the Australian bush, I probably should be boiling the billy instead of the kettle tonight.

Goodnight and best wishes,

Rowena Curtin

Reference

- Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 – 1946), Saturday 8 November 1924, page 61

Further Reading

Henry Lawson

The Drover’s Wife:

http://www.eastoftheweb.com/short-stories/UBooks/DrovWife.shtml

Water Them Geraniums: http://www.telelib.com/authors/L/LawsonHenry/prose/joewilsonandmates/watergeraniums1.html

Past Carin’

Well! I’m glad she didn’t get to go away with Bill, even if he hadn’t been her half brother. He obviously wasn’t a very nice man, although maybe the author gave too much away about him and could have more subtly let us draw our own conclusions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s interesting that you mentioned Bill, because when I read the story, I was very much focused on the aunt. My great grandmother adopted her sister’s daughter after her parents died, and I’ve heard she brought her up with very little love and the same happened when Geoff’s aunt went to live with her mother’s sister after their mother died when she was two. They all did their duty, but not much love and affection.

Have you read “Three Little Maids”? My copy arrived during the week, and I’m going to start exploring it next. I’s a bit intimidating to tackle Seven Little Australians and I’m going to read “Little Mother Meg” first. Read the three of them.

Hope things re going well with you.

Best wishes,

Rowena

LikeLike