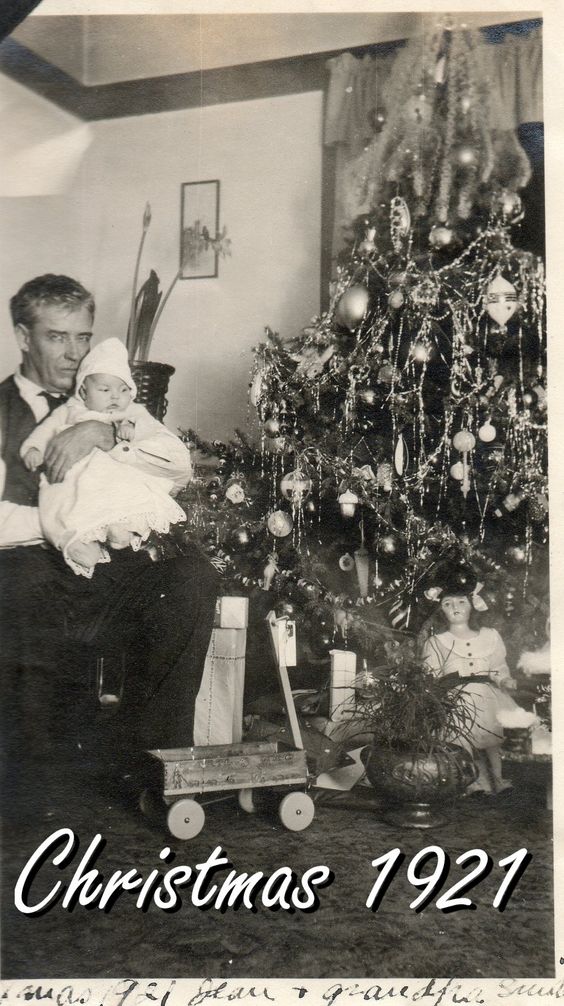

No doubt, it won’t surprise you that I never intended to spend Christmas 2021 with Ethel Turner reconstructing Christmas 1921. To be very honest, I’d planned to spend Christmas Eve at Church, and Christmas Day with the whole shebang over at my aunt’s place. A regular Christmas over there can attract over thirty people with bodies in and out of the pool, and enough food to sink a battleship.

However, covid struck again. On Christmas Day alone there were 6 379 cases of covid detected in NSW. Church was cancelled entirely. Mum and Dad are in their late 70’s and went into isolation, and decided not to go to the big family Christmas. I couldn’t be sure our kids wouldn’t infect the family in Sydney, or that they’d unwittingly infect us. So, the four of us stayed home, and were mighty grateful for the three dogs to add to the head count. It was our year to go with wisdom from the Wizard of Oz: “There’s no place like home.”

Anyway, as I said, I didn’t intend to go back in time and spend Christmas 1921 with Ethel Turner and her band of Sunbeamers. However, that’s where the research trail took me. Besides, there’s been a lot of talk comparing 2020 to the 1919 Spanish flu pandemic, and I’ve just brought it forward another year.

Before I launch into Ethel Turner’s 1921, a bit of context might be helpful. I’ve covered that over at my other blog, Beyond the Flow, here: https://beyondtheflow.wordpress.com/2021/12/28/christmas-1921/

However, Charles Dickens seemed to sum it up well with his timeless genius:

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way.”

Moving on to Ethel Turner…

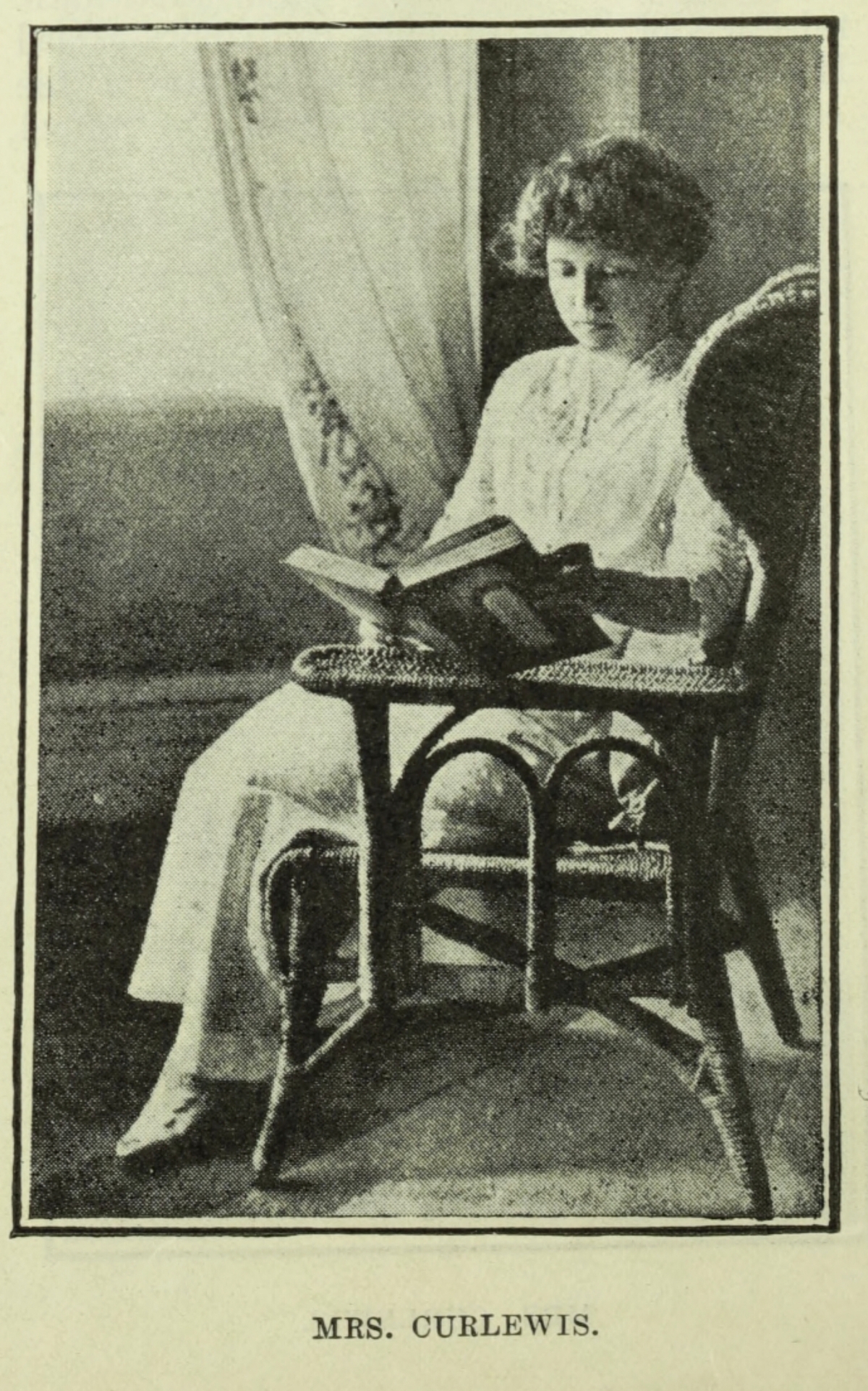

Born on the 24th January, 1870, Ethel Turner was 51 years old in 1921, and a year younger than I am now. She was married to Judge Herbert Curlewis and they were living at their home in Avenel, Mosman, Sydney although they spent Christmas 1921 at Palm Beach. Daughter, Jean, was twenty-three, and son Adrian was twenty and studying Law at Sydney University. By Christmas 1921, Ethel Turner had had 22 of her handwritten novels published, and King Anne was her offering for the year. She was famous.

However, for Ethel Turner it wasn’t the empty fame of celebrity. Rather, there was a strong sense of purpose and a desire to make a difference, and do good. While I can be dangerous to interpret Three Little Maids as being purely biographical, there is also much truth and Dolly (who is said to be Ethel) made this statement on becoming an author:

“One night…I felt I must do something. I felt I couldn’t just go on doing little things always,-staying at home and helping, and going to dances, and playing tennis. I used to think I should like to go as a missionary, – not to China, of course, only somewhere here where people were very poor and miserable. But that night I didn’t seem to want anything but to write books that people would love to read, and that might do them some good.[1]”

This aspect of Ethel Turner is often lost….the visionary, the world-changer, the woman who had experienced severe financial hardship as a child and travelled across the world for a better life, worked hard and overcome. She’s simply viewed through the lens of Seven Little Australians as though she were a one book wonder. Indeed, it appears that the massive difference she made to the lives of children through the series of children’s pages she edited has been forgotten, along with how she nurtured the artistic and literary abilities of younger generations through these pages. She was such an inspiration!

The trouble is that it’s very hard to condense an inspiration into a few lines or words to satisfy those who don’t want to immerse themselves more fully into the longer story. However, in this instance, can I caution you to sit down. Make yourself a cup of tea, and in the words of the great Molly Meldrum: “Do yourselves a favour!”

We’re going to pick up with Ethel Turner on the 20th November 1921. Sunbeams had only been launched on the 9th October, 1921, and just over a month old, and still in the nest. Yet, that didn’t stop Ethel Turner from launching an ambitious plan to make a difference that Christmas:

“FROM A CHAIR IN THE SUN

ABOUT SUN FAIRIES

Dear Young People, — One of the many tastes we have in common, you and I, Is our love for conjuring tricks. Here is one I particularly want you to try. Take a child with the corners of its mouth right down and its eyes running over with tears (there are any amount of them in the hospitals and crowded back streets, alas). Go up close to it, and with a quick sleight-of-hand slip into its fingers a tiny doll as pretty as a fairy. In less than half a minute the eyes will dry and the mouth corners go up. This trick has never been known to fail. So now then, let us do it together. Your part is to buy a tiny celluloid doll or kewpie, dross it in something very fairylike — gay and pretty, or comical as an elf — put it in a, tiny box, and post or hand it in to “Sunbeams.” My part will be to find the children in the hospitals and back streets about Christmas time. I shall also examine the dolls carefully — we will call them Sun Fairies— and give three prizes of half-a-crown each to the three most attractive ones, and six “Sun” honor cards. You need send no coupon with this competition, as the doll will cost you anything from twopence to sixpence. Send December 1st.

Yours ever,

Ethel Turner[2]”

Ethel Turner received an enthusiastic and touching response to her call for contributions. On the 11th December, 1921, she wrote:

“THE SUN FAIRIES

ROOMFUL OF WONDERFUL DOLLS DAME MARGARET DAVIDSON’S WINNERS

The response to the “Sun” fairies competition was splendid and many little “Sunbeams” will be cheered by the really wonderful little dolls sent in… It was a lovely spirit which prompted the competitors to send in the dolls — they were not concerned with winning prizes, but with doing something with their own hands which would give pleasure to children, to whom dainty dolls are a rare and precious luxury. Many of the children marked their entries: “Not sent in for a prize,” and pinned to almost every doll was a pretty little greeting to the recipient. They sat about all over the floor and the chairs and tables rather impatient in their boxes, just as trapped butterflies might be; they were eager to be gone upon their task of carrying sunshine. They were dressed in silk and spangles, in little frilly skirts of lace, in bridal gowns; in elf costumes; there were little mother fairies with tiny children around them, father fairies, fussy and important, fairies with opera cloaks on, and carrying bags; baby fairies, red riding hood fairies; one or two arrived with their beds and bedding, a few with suit-cases for the week-end and complete wardrobes. Wendy came, together with John and Michael, and Peter Pan. And wands! There were enough wands to have enchanted all Sydney and turned it to happy ways had they been held up. And no one, not any one, had forgotten the pretty little card with “From one Sunbeam to another” and other affectionate greetings. Dorothy Makin’s box of dolls, which won first prize, lacked only the bride groom to make the wedding party complete. But then it is so difficult to make a fairy-like creature of a man who should be dressed strictly in black. It was a rainbow wedding, and the bride chose ivory satin for her gown. She also had an overskirt of lace, and trimmed her whole frock with pearls. She wore the usual wreath and veil, and carried a bouquet of white blossoms and a fan. Her maids were frocked in rose, mauve, coral and eau-de-nil silk net, and wore quaint filets round their heads. Just by way of being different, they all carried fans instead of bouquets. Five little fairies, in five little boxes with five little Christmas cards, were sent by Betty Blake, who was second prize-winner. Betty dressed her fairies in white lace, showing beribboned petticoats. Glinting beads of gold and silver shone like spangles on the little dolls which will gladden the hearts of sick children on Christmas Day. Betty Grimm’s Sunbeamer was dressed in her party frock of rose-colored silk net, and she carried a lovely curling white feather fan. (But even fairies cannot live in party frocks all the time, so Betty sent along a box full of neatly made clothes for everyday wear, and did not forgot even a tiny tin of powder to powder her nose.[3]”

Of course, this touching story of generosity and human kindness is not complete without hearing about the sun fairies final destinations:

“THE SUN FAIRIES: How The Kiddies Loved Them”

I know that all of you who made a “Sun” Fairy will be delighted to hear how much joy they gave to the children who received them. Here are two letters which tell you all about them:–A.I.F. Wives and Children’s Holiday Association.

Furlong House, Narrabeen. Dear Sunbeams, — The dear little sun fairies arrived quite safely, and as fresh as when’ they left the designers’ hands. I am sure if the little donors could have seen the pleasure they afforded when received on Christmas Day they would be delighted to know they were indeed sun fairies in so much as they made radiance shine from each receiver’s face. With all good wishes to the Sunbeams from all the soldiers’ children at “Furlough House,” Yours sincerely, Ruby Fowle, Matron The second letter comes from Mrs Lyster Ormsby, who in the crowded streets of the city has for years sought to bring joy and sunlight into the lives of the little children there. Soup Kitchen for Little Children, 40 Burton-street, Darlinghurst. Dear Little Sunbeams,— I want to thank you for the dainty little ladies, fairies and babies the came to the Soup Kitchen during Christmas week. They came all neatly tucked away in a box, and was told they were to be given to some of the poor little’ girlies that I know as presents from “one Sunbeam to another. Well it happened that some of my little pals were hanging round when I unpacked your box and if you could have heard the “O-o-ohs” and “A-a-ahs” of admiration that came from them as I drew each dolly out of the box, you would have felt that you had sent a real sunbeam along. I gave your dollies away in many different quarters, and I feel sure you will be glad to know that each and every one received a warm and loving welcome from the new mistress. Among my little Soup Kitchen Girlies was one who has just left school and so felt too big for a doll. She always has a real live baby in mind-but still I could tell by the look in her face that she was just envying all the smaller girls; so I picked out a tiny kewpie doll that had been so prettily dressed in baby frills and I said: “I know you’re fourteen, Alice, and too big for dolls — (she thinks she is, you know) – but this is a Kewpie for luck and it goes on the rail of your bedstead. Would you like it?” She just loved it, and rushed off home to put it on her bed right away, “Good-bye, little Sunbeams, and a happy new year to you all from Inys Ormsby.[4]”

And now we’ll back peddle just a little, and read Ethel Turner’s Christmas Day letter to her Sunbeamers:

A VERY MERRY XMAS FROM A CHAIR IN THE SUN

Christmas Day

Dear Young People,—

Do you know Anna? What Anna? Merry Christmas anna happy New Year. Yes, I know this is the seventh time you have been asked this same joke, but that is the best about Christmas Day, isn’t it, there is such a rosy, kindly light everywhere, that you are ready to smile seven times at anything and everything. I hope that you are, every one of you, as happy as larks to-day: the boy with the sixpenny humming top, as well as the one with the expensive aeroplane. Happiness, real lark-like happiness, isn’t a thing to be bought with money; it is a thing right inside you. There is really an amazing amount of it lying about free in a sunshiny land like this; believe me it is not shut up in those expensive toyshops, pleasant though those places are. Happiness is just a little light, bubbling thing that you make for yourself, just as the lark makes its song. Good-bye till next week. Do you know Anna?

The Sunbeamer[5]

I hope you have been each to absorb each of these letters word by word, and truly absorb an Ethel Turner who might appear idealistic, utopian and off with the very fairies she was passing on. However, aim low has never had much of a ring to it, has it?!!

So, I hope you and yours are managing to find some of that lark-like happiness this Christmas and carry it into the New Year as well.

Best wishes,

Rowena Curtin

References

[1] Ethel Turner, `: Pg 302-303.

[2] Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 – 1954), Sunday 20 November 1921, page 2

[3] Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 – 1954), Sunday 11 December 1921, page 2

[4] Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 – 1954), Sunday 15 January 1922, page 2

[5] (Sydney, NSW : 1910 – 1954), Sunday 25 December 1921, page 22