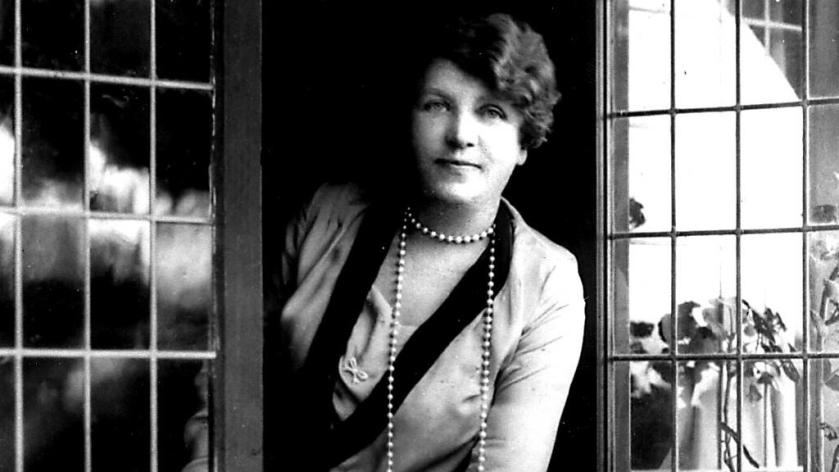

In so many ways, Australian author Ethel Turner needs no introduction. Yet, at the same time, as generation follows generation, a reminder is usually in order.

However, that is only partly why I am here.

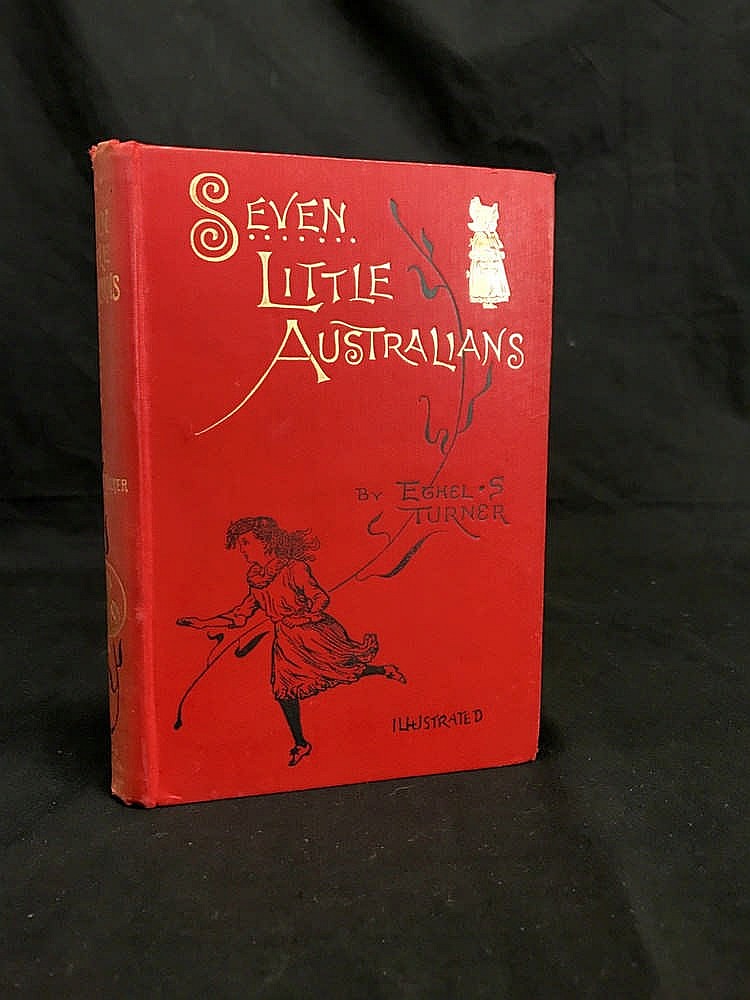

Although Ethel Turner is best known for her iconic first novel: Seven Little Australians, she was so much more. That is what I’m aspiring to share and discuss here at Tea With Ethel Turner. Moreover, I want to assure you, this is not a one person job either. Indeed, it’s rather daunting researching and being so incredibly inspired by the author of 40 novels, diaries, children’s columns, poems, newspapers. There is no end to Ethel’s writings. She was incredibly prolific, and the quality of her work was sustained throughout her life, at least from what I’ve read so far.

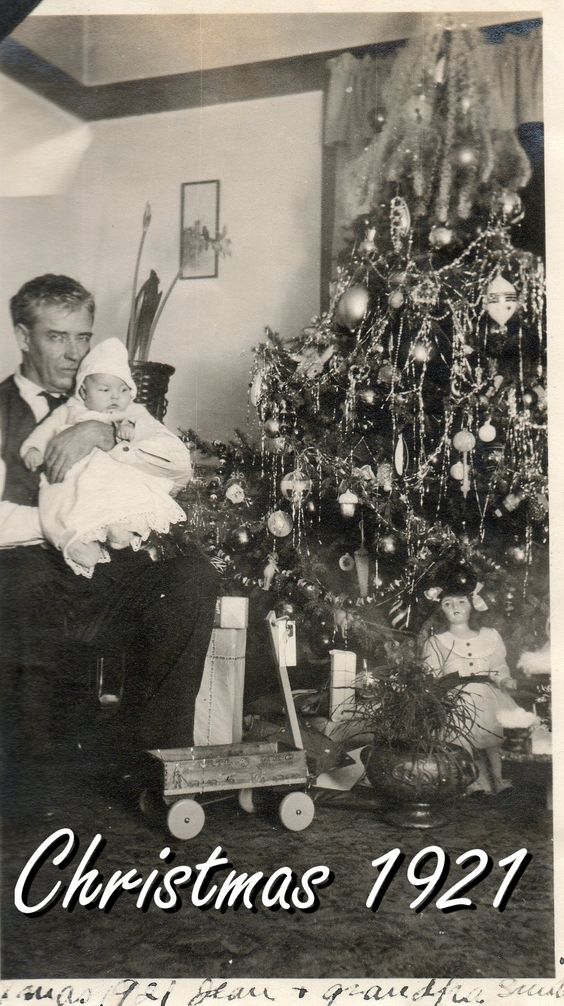

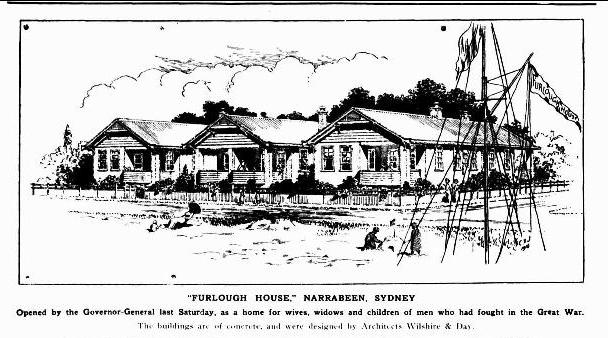

I found myself revisiting Ethel Turner via quite an oblique route during the current Sydney covid lockdown, which began on the 26th June, 2021. I have been spending the best part of the last two years since the 2019 bushfire crisis and the subsequent covid pandemic researching and writing up the biographies of Australian soldiers initially serving in France, but then I later went backwards in time to Gallipoli. That was all inspired by the school history Europe trip our son was due to go on last year. He was due to commemorate ANZAC Day at the dawn service at Villers Bretonneux and I wanted him to know about our family members who served there. Needless to say, my research project rapidly expanded, and that our son’s trip was cancelled.

Fast-forwarding through to 2021, I came across this letter addressed to Ethel Turner’s Sunbeam’s page:

A NURSE

“When I grow up I would like to be a nurse, so that I could look after poor sick people. If there happened to be another war I would go and look after the wounded soldiers. My daddy died of wounds at Gallipoli, where there were not enough nurses to look after the soldiers. I would love to wear the nice clean uniform of a nurse, and be in the children’s hospital amongst the little sick babies, as I love babies, and I don’t like to hear them crying. When I see the returned nurses with their badges I feel sure I am going to be one. I hope little girls will want to be the same so that there will be enough nurses for the poor soldiers if any more wars begin.

— Souvenir Prize and Blue “Sun” Card to Brenda Taylor (9), Greenock, Piper-street, Leichhardt — a little girl gallant enough, after her loss, to want to continue in the footsteps of her heroic father[1].”

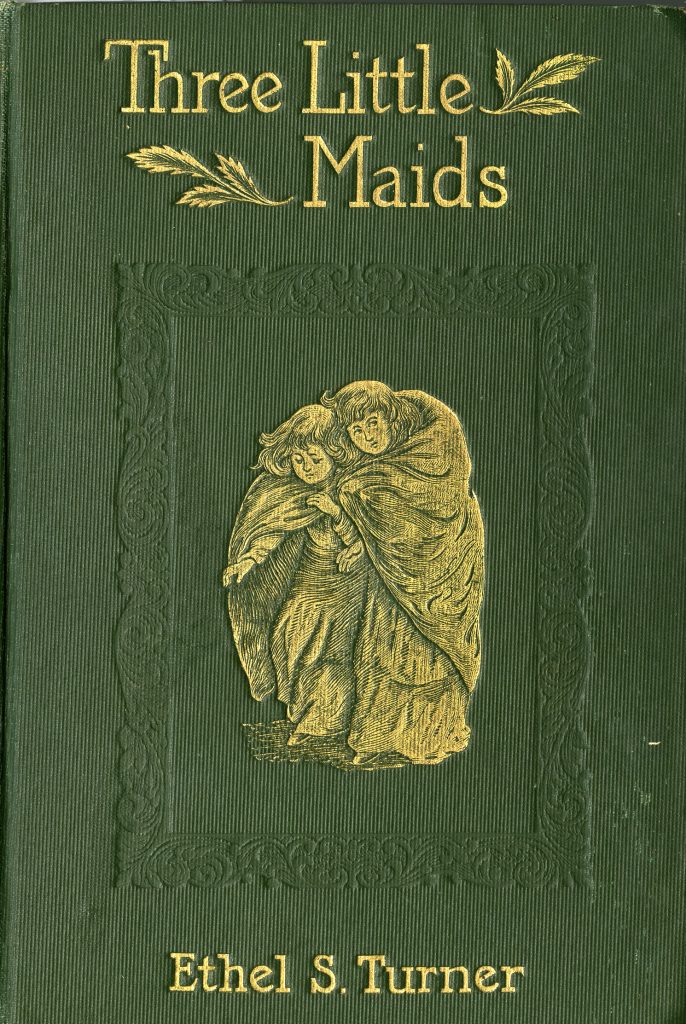

This was where I decided to take what I thought would be a short break from Gallipoli to explore the Sunbeams, and also re-read Seven Little Australians. Since then, I’ve been clicking away on eBay and anxiously awaiting my Ethel Turners to arrive in the post. So far I’ve also read The Family At Misrule, and The Cub is lined up alongside Captain Cub, Three Little Maids and I’ve currently studying Philippa Poole’s compilation: The Diaries of Ethel Turner and A.T. Yarwood’s biography From A Chair In The Sun. I’m being very patient because I’m sorely tempted to order Mother Meg so I can complete the Woolcot trilogy. However, I haven’t just bought these books to look pretty on the shelf. I want to understand Ethel Turner as a writer. What created her? What inspired her? Who was she and what did she mean to the readers of her books and children’s columns?

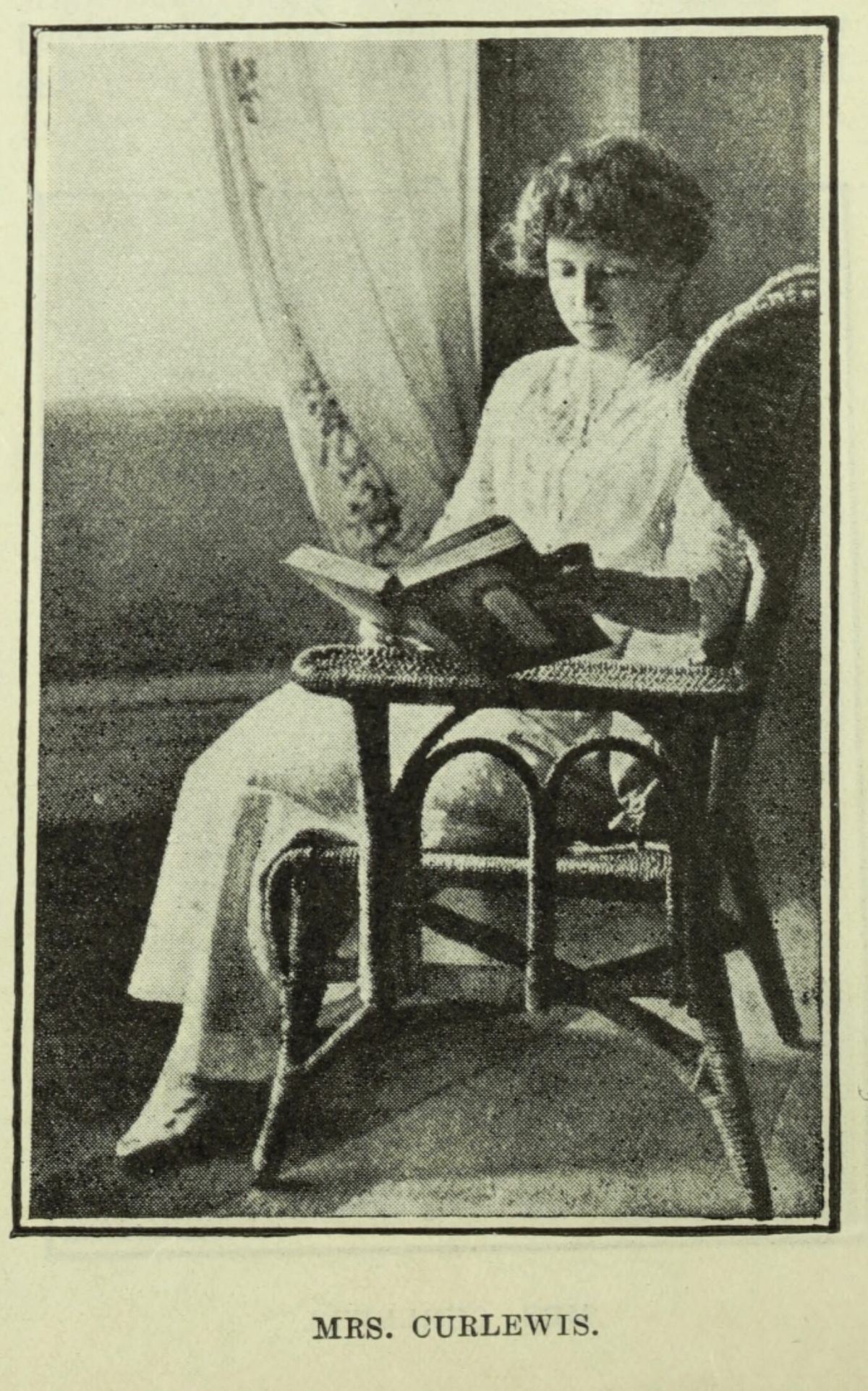

While I have just started out on this journey, albeit in a rather obsessed books and all manner, I would like to paint a portrait of an Ethel Turner who was a philosopher and educator as much as an author. She created worlds and decided which characters lived and died most famously in Seven Little Australians where the much loved Judy suddenly dies, and in the sequel where Baby and Meg also stare death in the face and I won’t spoil the story by saying anything more. Ethel Turner also wrote through the depression of the 1890’s, the horrors of the Great War. Moreover, she stopped writing novels in 1930 following the death of her adored daughter, Jean Curlewis. Ethel Turner had also faced death with her own tragedies losing her father when she was two, and her step-father when she was eight. Life wasn’t meant to be easy, but did it have to be that hard?

I warn you that this blog will not be written in any great sequence, and will jump around a bit. For better or worse, that’s the way my mind works and thankfully I can categorize my posts into some kind of order as I go.

Lastly, let me introduce myself. My name is Rowena Curtin. I have considered myself a writer since I was about ten and writing stories at Galston Public School in Sydney’s Hills District. I went on to attend Pymble Ladies’ College where I also studied Speech and Drama. That was how I first came across Seven Little Australians, when I was about 12, and I had to memorise and recite a passage of dialogue from the book. Being an all-girls’ school, Ethel Turner was very popular although I don’t remember the death of Judy, which might suggest I hadn’t actually read the whole book. During high school, I wrote anguished poetry about unrequited love, which I surreptitiously shared via notes in class. Thank goodness they weren’t intercepted. I attended the University of Sydney 1988-1991. I graduated with Honours in History, looking at the arrival of Modernist art and literature in Australia, but I had also studied Australian Literature and Australian Women’s History. During my time at Sydney University, I was president of the Sydney Writers’ Society, Inkpot for two years performed my poetry on campus, at Gleebooks, Chippendale’s Reasonably Good Cafe and various festivals.

In 1992, I finally managed to escape to Europe where I went backpacking for a year. One of the highlights was spending a month in Paris which included a solo poetry reading at the famous Shakespeare Bookshop then owned by it’s legendary eccentric proprietor, George Whitman. I returned to Australia and put poetry on the shelf to pursue a career in marketing. This trajectory was only altered by an acute, life-threatening auto-immune disease and while I was in hospital, my husband brought in my laptop and I started writing seriously again. While exploring writing for children myself, I moved onto biography and historic research. I have also been producing what I guess is a reasonably successful blog at Beyond the Flow: https://beyondtheflow.wordpress.com/ I am also married with two teenagers and three dogs. Our house is the personification of “Misrule”.

Lastly, I am also viewing Ethel Turner through a different lens. My father is actually one of seven children himself. So, I have some familiarity of what it is to come from a large family. Moreover, my dad’s youngest sibling is only ten years older than me. So, I sort of tacked onto the end of the original family in a way, and unlike my younger cousins have crystal clear memories of the family home.

However, the parallels with my dad’s family don’t end there. My father’s mother was international concert pianist, Eunice Gardiner. How she managed to have seven little Australians and still continue her career, has been a personal quest. As a fifteen year old, Eunice won the Vicars Travelling Scholarship and a year later after much fundraising, she left to take up a scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music in London with her mother as chaperone. In 1940, they returned to Australia during the London Blitz with Eunice under contract to tour with the ABC under the famous English conductor, Sir Thomas Beecham. In December, Eunice married my grandfather with a miniature grand piano on their wedding cake. Eunice speaks confidently in the press about continuing her career after marriage, which she stuck to despite her brother’s doubts. After the war was over, she spent a year in New York and Canada leaving the three boys at home. The eldest were sent to boarding school in Bowral while my Dad aged three remained at home with Dad, Gran and a housekeeper.

After returning to family life, Australian Consolidated Press sent Eunice to cover the Festival of Britain and the opening of Festival Hall in 1951. She told me how she loved having a doorman and a bit of luxury over there and (reading between the lines) a break from being Mum. By this stage, there were four young boys at home. No doubt, in common with Ethel Turner, my grandmother struggled with juggling her almighty talent and passion for music with the love of her family. It was never an easy balance. She loved both passionately.

I don’t know where my cups of tea with Ethel Turner will take me. Moreover, I don’t know where they will take you either. However, just looking at the very shallow depths I’ve dipped into so far, we can only be changed. Changed for the much better as well.

I look forward to sharing this exhilarating journey with you!

Best wishes,

Rowena Curtin

Sources:

[1] Sun (Sydney, NSW : 1910 – 1954), Sunday 30 July 1922, page 2